Modeling Ocean Waves

One’s first thought when considering ocean waves might be those that roll gently up our beaches, providing endless entertainment of surfers, body boarders, and beach goers alike. However, waves drive many processes along our coastlines including, beach erosion, coastal flooding, and alongshore transport of sediment, larvae and pollutants. Additionally, large wave energy provide a significant hazard to coastal infrastructure, beach goers and commercial and recreational boating. Therefore accurate, unbiased, high-resolution nearshore wave predictions are needed by both local communities and researchers. I am working on machine learning approaches to improving short-term wave forecasts (nowcasting), assimlation methods for wave buoy observations, and modeling frameworks to estimate flood hazards during high water levels and large waves.

Deep learning for wave nowcasting

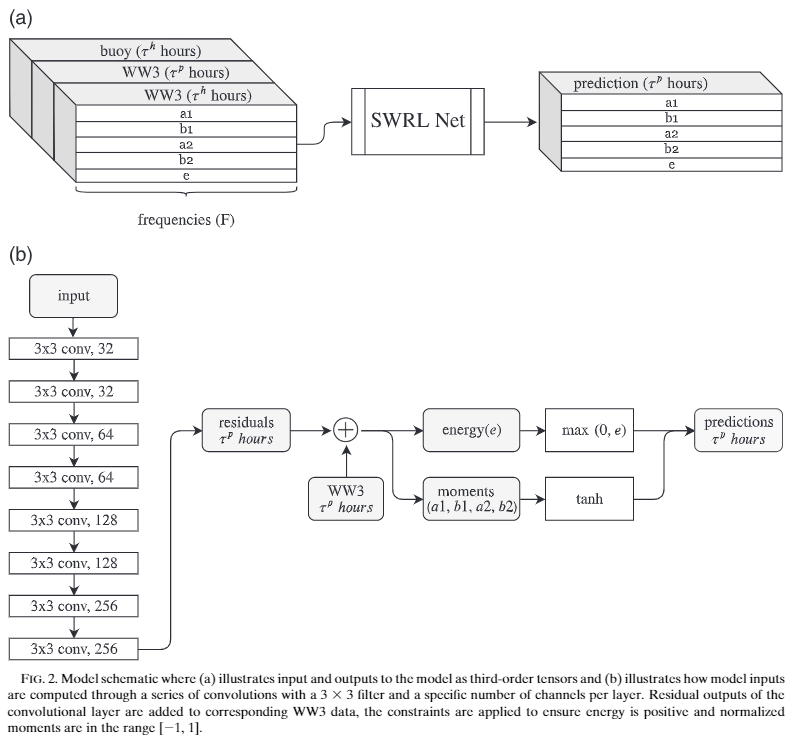

Recent advances in computing power, including GPU parallelziation, has allowed for the training of deep neural networks are large datasets with relative ease. With my colleague Brian Hutchinson and Western Washington University computer science students we are developing methods to correct recent wind and wave forecasts with trained neural networks. Recent work with convolutional networks suggest that forecasts can be correct up to 24-hours into the future with a relatively simple architecture using just a single buoy observation location. The model, SWRL Net, is illustrated below

Here a residual correction factor is determined as a function of frequency for each of the directional wave buoys observed moments. This detailed wave information is needed to initialize local models of wave propagation and run-up at the shoreline. On-going research is focused on applying perciever networks to many observation locations over the coast of Washington and Oregon State.

Modeling coastal flooding in the Salish Sea

Estuaries and bays are protected from a majority of remotely generated wave energy, however, storms events, characterized by low pressure systems and strong pressure gradients, produce near hurricane wind force that drive significant local wave generation. For example, on Dec 20th 2018 winds approached 60-mph generating strong waves throughout the Salish Sea. Wave run-up reached the grass at Marine Park in Bellingham (image at left), moved rocks and wood debri onto the Lummi Shore road, destroyed the ocean-side lane of Birch Bay drive, and caused serious damage to the Bay Breeze restaurant in Birch Bay.

As part of a larger U. S. Geological Survey effort to model coast line hazards I am developing approaches to downscale global climate simulations to local scale flooding. The Coastal Storm Modeling System CoSMoS is currently being implmented in the Puget Sound. Long-term regional modelling of water level and waves forces local scale wave run-up and flood models. Predictions identify coastal flood risks for local communities. For example, model outputs illustrate infrastructure at risks to flooding during a 100-year storm event after 0.5 meters (1.6 feet) of sea level rise.

Assimilating offshore waves into nearshore predictions

Along open coastlines incident most wave energy is generated by distant storms and dissipates at the shore. On partially sheltered shorelines, wave predictions are sensitive to the directions (e.g. animation on left) of onshore propagating waves, and nearshore model prediction error is often dominated by directional uncertainty offshore. I developed methods to estimate very-high resolution offshore directional wave spectra by assimilating global wave model predictions National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and in-situ buoy observations.

The methods developed will aid in rational buoy network design. Initial method development focused in southern California where the California Data Information Program maintains a dense buoy network. These observations act as a large incoherent array, provides strong directional constraints on the offshore wave spectra. These methods are applicable all along the western US coastline, and are currently under development for the Washington coastline. Wave transformation is rapidly modeled by linear transformation using backwards ray tracing. Ray-tracing provides improved results over typical wave models (e.g. Crosby et al, 2019) and methods are becoming available in a public repository (Ray Tracer).